A Walk on Monte Ceceri

Breathing in the mountain air in the footsteps of Leonardo da Vinci and admiring stone quarries in use since Etruscan times is a rare privilege, but if you live in Florence you just need to go out for a walk outside the city. Let us tell you about our experience (and Amanda’s) discovering Monte Ceceri.

We set off with a rucksack, water, fruit and trekking shoes, in the company of our dachshund, Amanda the Trooper, who, as always, is more lively than us and never backs down, not even when it comes to climbing. Our destination is Monte Ceceri, whose name derives from the swans that lived there and were called “céceri” (Italian for “chickpeas”) due to the black protuberance on their beak that looked like a chickpea. It is a hill of about 400 meters located between Fiesole and Settignano, in the green area surrounding Florence.

Vista su Firenze

We park on via Benedetto da Maiano, dedicated to the well-known Renaissance sculptor and architect or, as they say around here, “stonecutter“. The whole area (which consists of about 40 hectares) is characterized by the presence of stone quarries, the most used building material in Renaissance Florence. The quarries, scattered throughout the mountain, were used since the most remote times: the nearby city of Fiesole, of Etruscan foundation, has a wall still visible built with this massive, albeit extremely ductile, rock and the Romans used the same boulders to create their colony here, providing it with spas, temples, roads and the magnificent theater still entirely visible. In the Renaissance, Giorgio Vasari used the same stone to build the Uffizi Gallery and Michelangelo himself used to say he had taken on his talent as a sculptor by sucking milk from the nurse who lived in this area. In more recent times, the stonemasons became proud anti-fascist partisans and, in protest against the regime, they retired to their mountain quarries refusing to mingle with the black-shirted populace of the city.

We take the path that opens into the green countryside at the foot of the mountain and we walk towards our destination, Piazzale Leonardo da Vinci, a place that, according to tradition, Leonardo used to test his prodigious flying machines. To get there, you have to follow paths with decidedly exotic names (we took the “path of the gods”) and which open onto unexpected and seductive glimpses of the landscape. It is easy to understand why this area, in the 19th century, was chosen by the colony of infatuated foreigners as their favorite residence! On the horizon, beyond vineyards and cypress groves, we glimpse the romantic tower of Castello di Vincigliata, a dreamy castle built in the early 19th century by the very wealthy Anglo-Scottish patron John Temple-Leader.

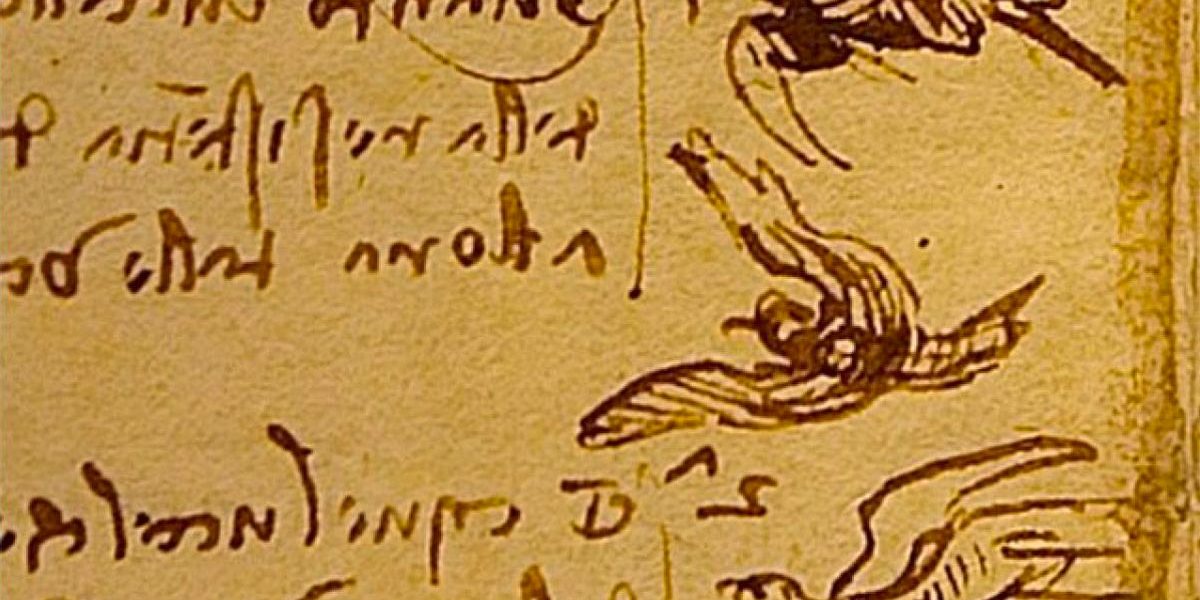

As we go up, I think of Leonardo and his obsession with flying. Leonardo produced over 500 drawings on flight and its mechanics, and developed his interest over 20 years of observations. The curiosity for flying began when he became an apprentice at Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop and continued throughout his career. The artist cheered up the aristocrats in Milan and France by designing mechanical birds that hovered in flight during elaborate sets that he designed. In his notes, Leonardo studies the body of birds, their anatomy and the shape of the wings, and following his observations which he collects in his Code on Flight, he is convinced that it is possible to build a flying machine!

Ascending in the silence of nature, interrupted only by the few adventurous explorers we meet (and with whom Amanda immediately forms a brief but intense friendship) I think Leonardo could not have chosen a better place to conduct his experiments on flight. I can almost imagine him, with his bags full of notes, his cars and his tools, walking briskly towards the top of the mountain, just like us. Moreover, the area is rich in avian fauna and, among the many species, Leonardo must have greatly appreciated the kite, which remains one of his favorite birds.

In this regard, I am reminded of the famous article by Sigmund Freud on Leonardo’s homosexuality which quotes a dream Leonardo had. In the dream, a kite landed on his face, while he was still an infant, and it struck the mouth with its tail. The father of psychoanalysis read a clear reference to Leonardo’s “oral fixation” and an incontrovertible proof of his sexual orientation. Freud was not wrong when he maintained that Leonardo was gay (after all, it has never been a mystery), but perhaps he exaggerates in his interpretation of his dream. What is certain is that Da Vinci was a fan of birds (in Italian, the word “bird” is used as synonym for “penis”).

After about 40 minutes of walking, we reach the summit and the view is spectacular. Observing the milestone placed here in memory of the scientist’s experiments, we also remember another character who accompanied Leonardo. It was Tommaso di Giovanni Masini da Peretola, known as Zoroaster. According to the historical records, Zoroastro was a magician, fortune teller, alchemist and hermetic philosopher. In the documents, Zoroastro is remembered as Leonardo’s apprentice boy and legend has it that it was he who tested the flying machine designed by the imaginative artist. In 1505, when the experiment was conducted, Zoroaster was in his thirties, ‘of great stature and handsome person’, with a ‘surly face’ and ‘proud look’, with a long black beard reaching chest, and surely Leonardo will have seen in him much more than a simple collaborator…

After about 40 minutes of walking, we reach the summit and the view is spectacular. Observing the milestone placed here in memory of the scientist’s experiments, we also remember another character who accompanied Leonardo. It was Tommaso di Giovanni Masini da Peretola, known as Zoroaster. According to the historical records, Zoroastro was a magician, fortune teller, alchemist and hermetic philosopher. In the documents, Zoroastro is remembered as Leonardo’s apprentice boy and legend has it that it was he who tested the flying machine designed by the imaginative artist. In 1505, when the experiment was conducted, Zoroaster was in his thirties, ‘of great stature and handsome person’, with a ‘surly face’ and ‘proud look’, with a long black beard reaching chest, and surely Leonardo will have seen in him much more than a simple collaborator…

The experience was not very successful (the machine apparently collapsed somewhere), but we, like Leonardo, are more interested in the idea than the result. The prototype now exists only in the drawings and in the imagination of historical reconstructions, but the principle that supports the research is fascinating. Leonardo’s mind, free from the constraints of the conventions of the time, hovers like a large bird and takes flight in a totally environmentally-friendly way.

The last sentence of the Flight Code, carved on the monumental stone in front of which we are standing, leaves us with a moving and wonderful memory of Leonardo’s experiment and passion, and delivers to posterity a beautiful ode to the Monte, to human ingenuity and to Nature:

“The great bird will take its first flight above the back of its great Cecero, filling the universe with amazement and all the scriptures with its fame, and giving eternal glory to the nest where it was born”.