Michelangelo Merisi (1571-1610), better known as Caravaggio, wasn’t just a notorious gay artist, but the leader of a veritable queer artistic revolution who enjoyed breaking the rules of traditional iconography while refusing to follow the teachings all artists were given. One of the aspects that best describe his character was his particular proclivity for choosing street boys and prostitutes as painting models. In a period when artists were supposed to look for inspiration in classical works, Caravaggio would point at the Roman crowd and say, “I already got my models”. Needless to say, this angered the bigots who found this practice shocking and totally inappropriate given that the vast majority of his patrons were members of the Roman clergy.

Evidently, Caravaggio never really cared much about judgment. Actually, it looks like he enjoyed being at the center of attention. When he moved to Rome from Lombardy, he became famous for his unorthodox naturalistic style which must have piqued the interest of the urban elite. Inspired by the Roman urban jungle, Caravaggio combined the hustle and bustle of the 17th century city with classical subjects only to disrupt the traditional way of painting and pave the way to a modern art which would appeal to the senses rather than the mind.

In his early works, commissioned by rich aristocrats, bankers and princes of the Church, Caravaggio often exploits the theme of a young adulthood to satisfy his patrons (who were probably gay themselves), and give them an erotically charged subject. Young seductive boys with their mouths half-open, their skin soft and white as a pearl, partially undressed to lure the viewers: these are Caravaggio beautiful ideal models, some of whom were his lovers, like Mario Minniti and Cecco Bonneri. As he knew only too well, sex always sells and in Rome, the capital of Baroque sexual decadence, it sold even more.

When he painted Bacchus (circa 1596), Caravaggio was living under the protection of Cardinal Del Monte, an eccentric character originally from Tuscany and a close friend of Grand Duke Ferdinando de’ Medici. Del Monte was so influential that Caravaggio endlessly bragged about his patronage and felt he could carry a sword just because he was his friend, even though he had no legal right (walking around the streets with a weapon was the prerogative of aristocracy). The cardinal was passionate about art, science (Galileo Galilei famously gave him one of his telescopes) and music plays. Concerts at his palace attracted many members of the Roman upper class – all men, of course – and sometimes a fair degree of transvestism was part of the entertainment.

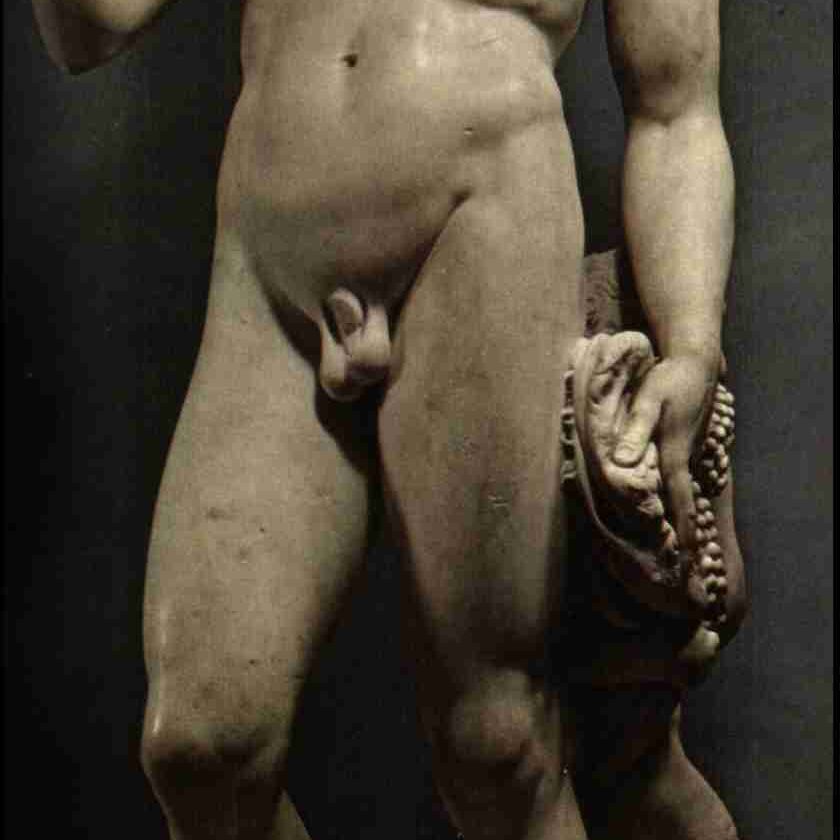

It’s not hard to imagine Caravaggio trying to please his crowd with ambiguous pagan subjects. His choice of Bacchus can be traced back to Greco-roman god’s popularity in the Renaissance, particularly with artists like Michelangelo who had sculpted a Drunken Bacchus for Cardinal Raffaele Riario in 1496 (unfortunately, the cardinal found Michelangel’s work a little too adventurous and gave it to the Roman banker Jacopo Galli). However, what strikes us in Caravaggio’s Bacchus is a realistic depiction of the god of wine and wilderness, less idealized than any other before.

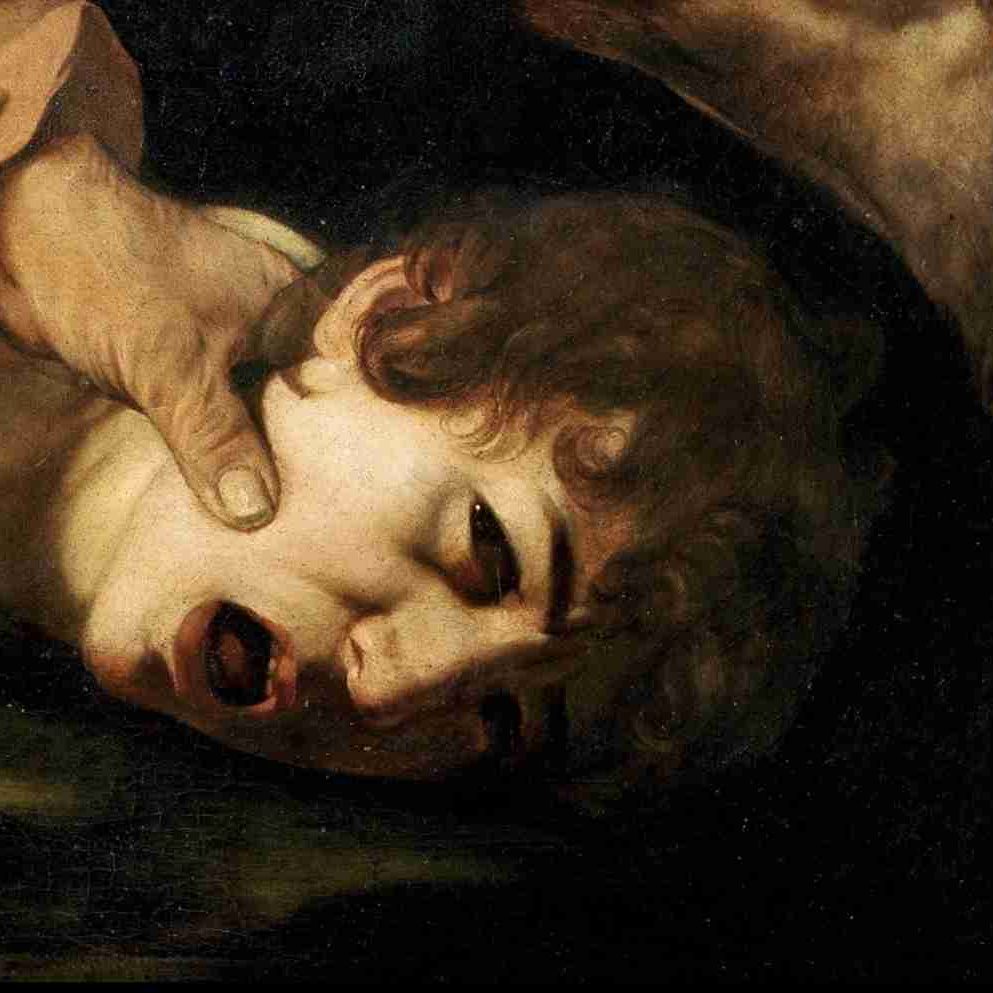

Bacchus was usually depicted standing, set against on open landscape, in the company of a satyr to define his role as both god and mentor. Caravaggio approached the subject differently, having Bacchus sitting on a couch, in a private environment that looks like the artist’s studio, about to take off his robe, which seems to be thrown carelessly on him. He is offering a glass of wine to the viewer and, from his rosy cheeks, it looks like he’s been drinking some himself.

The sexual innuendo may refer to the homosocial context of the cardinal’s entourage, but the fact that Caravaggio deprives the figure of his mentoring nature turning him into a young prostitute with dirty fingernails (and probably a dirty mind too) is even more interesting. Caravaggio deliberately disrupts the traditional iconography of Bacchus and gives us a modernized version of the myth, an intentionally queer figure who might be about to say, “Look, I’m no Roman god, I’m only dressed up as one”.

Don’t forget the symbolic layer! Caravaggio shows us a fruit basket where the fruit is slowly rotting away. If still lives were often included in secular subjects as tokens of the precarious nature of earthly things, the rotten fruit here could only mean that time goes by very fast. It’s Caravaggio’s ultimate way of telling us to hurry up and seize the day, because youth, like all things on the Earth, doesn’t last forever. All good things come to an end, so you’d better enjoy them while you can. And we certainly intend to!

Wanna discover more about Caravaggio’s queer masterpieces and career in Florence? Join us on our Uffizi gallery tour!