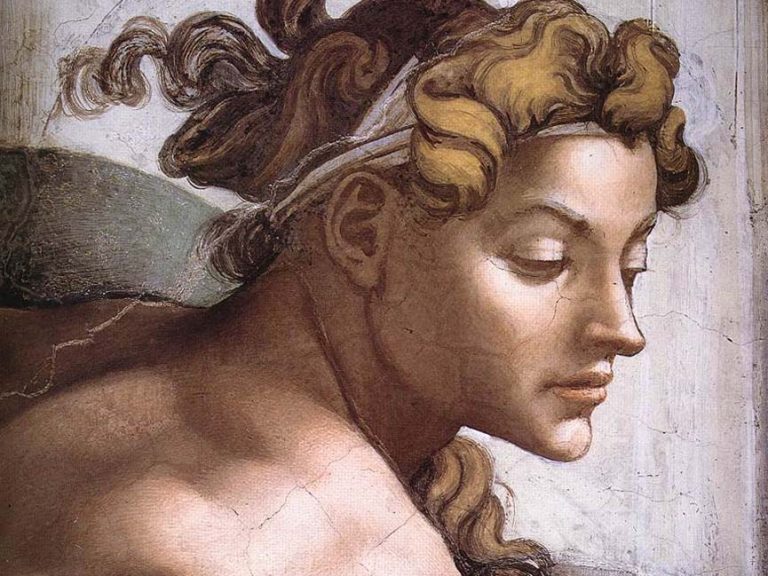

Michelangelo Buonarroti was not only the most brilliant artist of the Renaissance but also a sublime poet with a sophisticated and touching pen that reveals, between the lines, his deepest soul. In his letters, especially those written between 1532 and 1564, the portrait of a tormented, meticulous, impatient, stubborn, jealous and maniacal man emerges: in short, the portrait of a problematic and profoundly human artist, a victim of his own Love. After all, it is precisely love experienced as burning agony that pushes Michelangelo towards an art characterized by a restlessness and a lacerating dissatisfaction. Throughout the correspondence there is a sense of dissatisfaction and helplessness towards an art that has failed to represent the ideal of perfection so sought after by its contemporaries. The artist will express his failure by destroying all his drawings, precisely because he is aware that no one, after him, would have been able to convey his vision of the world.

A shocking encounter

One of the most shocking moments for Michelangelo that we can learn from his letters is the meeting with the young Roman nobleman Tommaso de ‘Cavalieri. He was born around 1510 in Rome, but had Florentine origins on his mother’s side, who was the daughter of the banker Tommaso Baccelli. He was 23 years old when he met Michelangelo during his stay in Rome, in December 1532, when the artist was 57. It was a sculptor, Pierantonio Cecchini, another Florentine living in Rome under the protection of Cardinal Ridolfi, who introduced Tommaso to the great master, perhaps because the young man wanted to receive drawing lessons or simply to be able to meet in person the most renowned and skilled artist of sixteenth-century Italy.

Whatever the reason for the meeting, we know that it shook Michelangelo to the core and led him to write, the next day, one of the most poignant letters of his entire career. In order to motivate the beginning of this correspondence, Michelangelo compares his decision to crossing a river, “as if I had to cross barefoot a water stream“, which at first appears to him tiny and therefore easy to wade. All of a sudden, without even realizing it, the river becomes a tumultuous and dangerous sea: “the ocean with the waves above appeared before me, so much so that if I could, in order not to be completely submerged by them, I would gladly return to the beach I left from”.

In this certainly fatal crossing, Michelangelo knows he is alone, isolated, and prostrates himself in total submission to his beloved. The confidence in such a difficult undertaking comes from the belief that he has found the true meaning of his own existence, that is, the other half of himself, a kindred soul.

Was Tommaso poetically “penetrated”?

Unfortunately, Tommaso doesn’t think so (or at least he doesn’t show it right away). In his reply, he takes on a courteous and detached tone, even though he reciprocates Michelangelo’s kindnesses. He promises to visit him soon if it weren’t for the fact that “fortune, in this only contrary to me, wants me to be unhealthy now that I could enjoy you“. The recourse to an unspecified illness offers Tommaso the perfect excuse not to meet Michelangelo since he, without a doubt, feels disturbed and, at the same time, attracted by the audacity of this bold man.

The two continued their correspondence and, in the subsequent letters, we witness a change in the writing both in language and style. Michelangelo’s letters become more possessive (when he goes to Florence, he is afraid that Tommaso will forget and neglect him) while Tommaso’s take on warmer and more friendly tones, almost submissive, which make us suspect that at the beginning of the acquaintance the young man has observed the rules of courtly love by behaving as a “courted woman” and, as such, reticent and shy, but who, once given to the court of her lover, gives herself to him. It is no coincidence that Tommaso used the same symbolic repertoire and even the same words as Michelangelo in his letters, welcoming the artist’s language into himself, in a kind of metaphorical poetic penetration.

Elective affinities

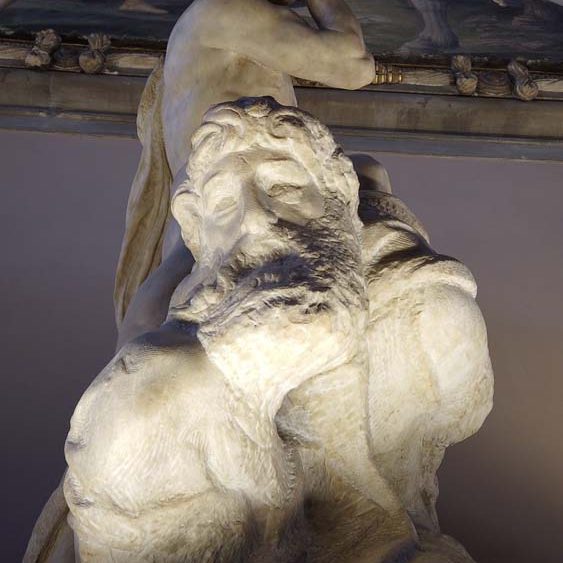

We do not know if the friendship between Michelangelo and Tommaso went beyond Platonism, because the most of their letters were set on fire, although it is legitimate to think that this was the case. Unfortunately, those curious about tabloid gossip will not find satisfaction because there are no explicit references in the letters in our possession! However, what we can say with certainty is that Michelangelo and Tommaso will have a fruitful exchange, creating a relationship of mutual esteem and affection. The artist will send him important and famous drawings, for which he will ask for his opinion, among which the Rape of Ganymede and The Torment of Titius (both of which can be seen in our Uffizi Gallery tour!), The Fall of Phaethon and The Bacchanal of Children stand out.

Even Duke Cosimo I, the new ruler of Florence, about thirty years later, would write to Tommaso to convince Michelangelo to provide him with at least one work (since Michelangelo had repeatedly refused his invitation to return to Florence). Michelangelo obviously refuses and Tommaso is forced, in order not to disappoint Cosimo, to “deprive me of one of my children”, that is, a drawing now preserved in the Florentine Museum of Casa Buonarroti depicting Cleopatra.

Michelangelo’s legacy

Tommaso de’ Cavalieri will be present during the last moments of Michelangelo’s life, who died in Rome, at his home in Macel de’ Corvi in 1564. The Roman nobleman had married and had children, one of whom, Emilio, will become an established musician, but the relationship with Michelangelo will always be crucial in his life.

In the same letter to Cosimo, Tommaso demonstrates his erudition by recommending a woman painter, Sofonisba Anguissola, to the duke himself. Tommaso _Tomsays he considers her style “not only beautiful but inventive“, showing an attention to female painting far ahead of its time.

Evidently, the relationship between Tommaso and Michelangelo was not just a flash in the pan or a simple friendship, but a relationship between two similar minds, a bond of spirit and body. Michelangelo’s homosexuality, which for centuries has been hidden and censored, appears to us, as an overwhelming and uncontrollable passion. We contemporaries cannot help but contemplate the legacy of this restless and tormented artist with absolute wonder.